While most people understand what a “trademark” is—a brand name, logo, or short phrase—many are less familiar with “trade dress.” But while less well-known, trade dress can be used to protect designs, either by itself or in a layered approach with patents. The layered approach requires attention to the intersection of these two forms of intellectual property protection. Otherwise, patent disclosures may undermine trade dress due to functionality concerns.

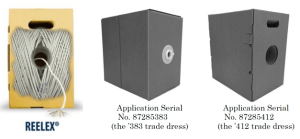

Reelex Packaging Solutions, Inc. manufactures winding machines capable of winding and packaging cables and wires into boxes. The packaging technique allows for easy removal of the cable or wire from the box with less likelihood of kinking or tangling. Reelex packages the cable and wire into a figure-8 formation and places it into “Reelex Boxes” as shown below:

Reelex filed two applications for registration of the box designs in International Class 9. The USPTO refused both because, as a whole, the designs were functional and therefore did not meet the legal requirements for establishing trade dress. To be protectable under Section 43(a) of the Lanham Act, trade dress must be both (1) non-functional and (2) distinctive. Failure to meet either requirement precludes registration.

The USPTO Examining Attorney refused the registrations based on Reelex patents that identified functional features and company advertising that described its “tangle-free technology” found in the boxes that it sought to protect. The USPTO Examining Attorney also found that the trade dress lacked distinctiveness.

The Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB) affirmed the Examining Attorney’s decisions on appeal by Reelex. The Federal Circuit affirmed the TTAB’s decision on a subsequent appeal by Reelex.

As to functionality, the Federal Circuit reviewed the Morton-Norwich factors: 1) existence of a utility patent disclosing the functional aspects of the design; 2) advertising materials touting the functional advantages of the product; 3) availability of functionally equivalent designs; and 4) assessing whether the designs result from a comparatively simple or inexpensive manufacturing method. In re Moron-Norwich Products, Inc., 671 F.2d 1332 (C.C.P.A. 1982).

The first factor – the existence of utility patents – was found to weigh heavily against Reelex’s box design. Reelex previously filed five utility patents covering the two different boxes and the winding technology, each of which disclosd the functionality features Reelex claimed as trade dress. These included the positioning of the “payout tube” (central hole for dispensing the cable) and the “payout hole” to minimize kinking and tangling; the construction and function of a payout tube and collar, which when snap-fastened together, smoothly guides the cable through the tube to decrease damage to the box and ease dispensing; a larger hole that provided additional advantages for use with larger diameter wire or cable; and cutout handles to enable easier transport; and the preferred sizing and dimensions of the boxes. Because of these extensive disclosures of the functionality of the claimed trade dress, the Federal Circuit found that the TTAB’s decision regarding the first Morton-Norwich factor was supported by substantial evidence.

Turning to the second factor – advertising materials – the TTAB had found that Reelex’s website alleged that the winding and packaging system made it easier to dispense cable and wire without kinking or tangling. Additionally, the system was lower cost and allowed for easier transport and storage of the boxes. The Federal Circuit found the TTAB’s finding to be based on substantial evidence, all of which further indicated functionality.

As to the third factor – whether alternative designs existed – Reelex argued that the TTAB had not sufficiently considered employee and inventor declarations. The TTAB gave the declarations little because the statements made were conclusory and contradicted by disclosures made in the patent specifications. Therefore, the Federal Circuit found the TTAB gave adequate consideration to the declaration and was within its discretion to give little weight to it.

As to the fourth factor – simple or inexpensive manufacturing methods – the Federal Circuit simply declined to consider it. The Court noted that the TTAB had found no evidence of record as to this factor and therefore agreed that based on the preceding three factors, substantial evidence weighed in favor of the trade dress being functional.

Consequently, the Court did not reach the issue of whether the trade dress had also acquired distinctiveness.

Thus, when considering how different intellectual property protections can be used in combination, one must consider how each can intersect and potentially undermine one another. A layered approach requires careful planning to determine the ramifications of patent application disclosures trade dress. Priority may need to be given to one type of protection, but considerations of each should be determined as early as possible to avoid findings that the claimed trade dress is functional.